C

Ask older New Orleanians where they were born and many will tell you it was Charity Hospital on Tulane Avenue. Affectionately known by locals and many throughout the state as “The Big Free” Charity embraced a colorful and unique place in the city’s history.

Established by a local French boat builder in 1736, Jean Louis was horrified by the plight of indigent people who had nowhere to go for medical care. As a result, he decided to leave all of his holdings to the founding and maintenance of a hospital. For over 250 years, Charity Hospital would continue to serve the poor.

From its beginnings to its closure in 2005, Charity has weathered many storms to maintain its status as one of the oldest, continually operating hospitals in the United States. It has withstood hurricanes, fires, the Civil War, financial woes, infectious diseases, the Huey Long Era, crumbling facilities, and integration.

This article will explore only one era in Charity’s past, the Jim Crow Era (1878-1964) and will discuss the effects segregation of the races had on black patients under its care.

Before the Civil War, black people were rarely taken to Charity Hospital when seriously ill. Slaves were considered valuable property and were cared for on the plantation where they lived or by physicians hired for plantation concessions. Even free people of color in the city used the hospital very little at that time.

Immigrants from dozens of European countries (particularly Germany & Ireland) were treated at Charity in its early days. Many arrived ill after their long journey and often appeared at Charity’s doors to receive whatever care they could get.

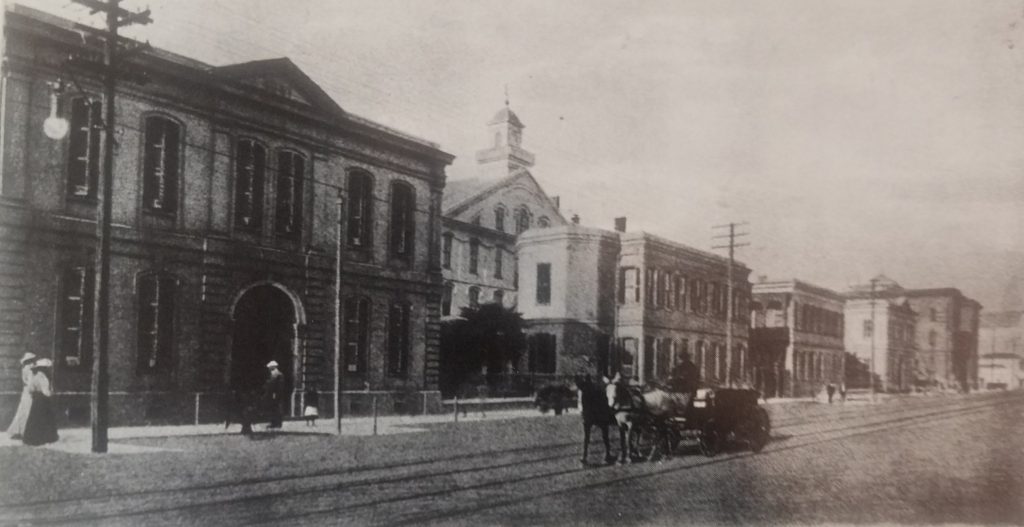

Charity Hospital (1835-1935)

The Jim Crow Era (1878-1964)

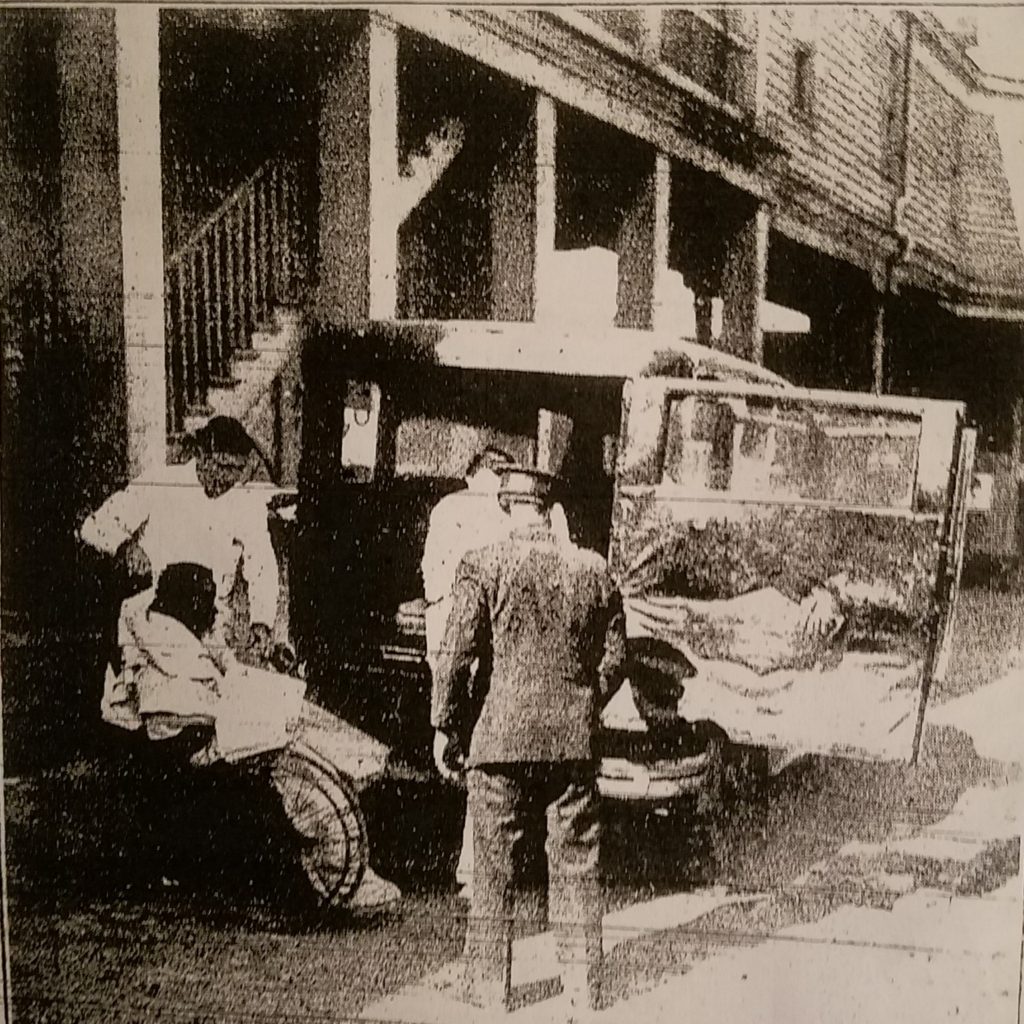

Charity’s Back Door Policy

In April of 1926, a sign was placed prohibiting members of the Negro race from entering through the hospital’s front door. They were told in the future to always use a back entrance on Gravier Street instead of the front entrance on Tulane Avenue.

One week later a mass meeting consisting of 300 black citizens met at the Pythian Temple. They appeared before the Board of Administrators of Charity Hospital and presented a petition requesting the board to rescind the order.

A committee of leading Negro citizens led the group. They were: O.C.W. Taylor, Walter L. Cohen, Dr. J. A. Hardin, Dr. G.W. Lucas, Hon. Rev. E.W. White, James Lewis, and T.T. Galbreth

The petition stated that since Charity was a public institution supported by black people as well as other citizens, and since it is a charity institution (not white charity nor black charity- just charity) and since Thomy Lafon, a colored man, contributes generously to your hospital; we would like you to rescind this order that you have casted upon us, the Negro citizens of New Orleans.

The petition ended with these words:

“All the good this hospital has done is about to be wiped out by this one treatment for white people and another treatment for black people, which is repugnant to our idea of what constitutes charity.”

The petition continued to be ignored by hospital administrators. It soon became known as Charity’s Back Door Policy.

A Louisiana Weekly article of June 15, 1963 (twenty-seven years later) reported similar conditions still in existence at Charity. A large group of individuals complained to the local newspaper that when they entered the colored admissions department of the hospital to secure eligibility cards, they found about 60 other blacks standing even though unoccupied chairs were still available. Those chairs were reserved and marked for whites only. Some patients had been standing from 8:30 a.m. to 3 p.m. Any one who attempted to sit were forced to move by the hospital’s watchman.

Segregated Wards

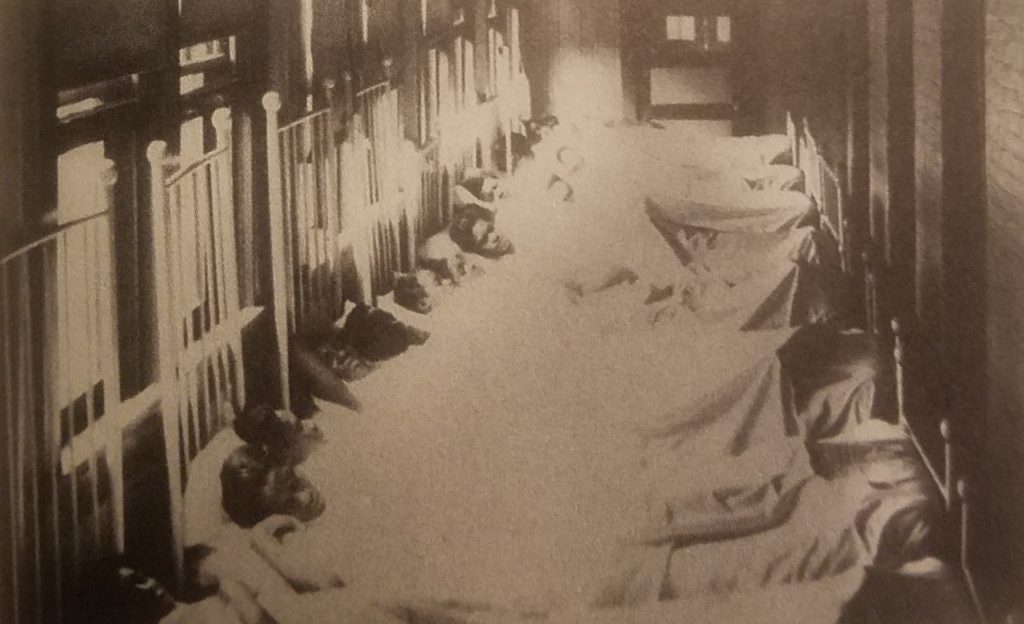

On Monday, September 30, 1936, while the old Charity building was being demolished to make way for the present-day structure, patients had to be removed to various other locations. Blacks, of course, had to be housed separately from whites. For two years during construction, black women were housed in downtown New Orleans at the Pythian Temple on the corner of Saratoga and Gravier.

The top floor of the seven-story Pythian contained a huge ballroom with a two-story ceiling. This section was used to house approximately 130 colored patients which had no dividing walls and absolutely no privacy. Two women were assigned to each single bed, facing opposite each other. When overcrowded, a third patient was positioned under the bed.

Even patients with active tuberculosis were placed on the open ward since administration could not locate separate available housing. Such primitive conditions were inhumane and often caused communicable diseases to spread throughout the area.

Blood Bank

Even Charity’s patients had to have their blood racially identified and stored. Charity had only one blood bank but, before 1965, the donor station was housed in separate colored and white areas. Blood was kept separate and labeled c (colored) and w (white). Of course, everyone knew to never give black blood to a white patient. Only in an emergency would white blood be given to blacks and in rarer conditions would the reverse be done.

Equipment

All of Charity’s facilities (public toilets, employees’ toilets, locker rooms, dining facilities, benches, water fountains, patient files, signs and even phones) were racially separated. Once the hospital was mandated by the Civil Rights Act of 1964 to integrate, Raymond Chapital of the NAACP insisted that inside the hospital there were certain black telephones for blacks to use and others for whites. He was told by administrators that such a statement was impossible since all phones were made of black plastic.

Chapital said, “I’m not talking about the color of the phone…You know what I mean. There are certain phones that only white people can use and certain ones that only black people can use.”

To prove his point, Mr. Chapital proceeded to check with a black orderly. Pointing to one phone specifically, the orderly firmly stated, “When I want to use a telephone, I can only use THIS one, not any other one.”

Politics

Politics also played an important role in achieving integration. Earl K. Long was one of the chief opponents of racial segregation at the hospital. Being a shrewd politician, he devised a plan to have more black nurses hired at Charity. He did this by insisting that it was very shameful and undignified for Charity’s white nurses to bathe black patients and perform other menial tasks. Many staff officials agreed and as a result, the hospital began to hire black nurses even though they could only serve black patients in segregated wards.

On October 27, 1936, Nurse Susie Keith suddenly took sick and died as a result of eating liver for lunch which had been mistakenly dipped in sodium fluoride, a deadly poison, instead of flour. Several other black employees (Henry Benjamin, Vincent Goins, Thomas Boutee) became sick but eventually recovered. Unfortunately, Miss Keith, after becoming very ill, was not given any medical treatment for an hour.

This incident was investigated by The Louisiana Weekly and it was discovered that white nurses who came on duty at 7am always received breakfast while Negro nurses arriving at the same time were not fed until lunch. By having to eat after the white nurses Miss Keith and her friends, had to eat what was left for lunch. Unfortunately, it resulted in her death.

People of color could not receive medical education or internship training at Charity during the Era of Jim Crow. As a result, many black doctors and nurses were forced to move out of state for training. This continued until Dillard University in 1932 established Flint-Goodridge Hospital on Louisiana Avenue, staffed by black nurses and doctors.

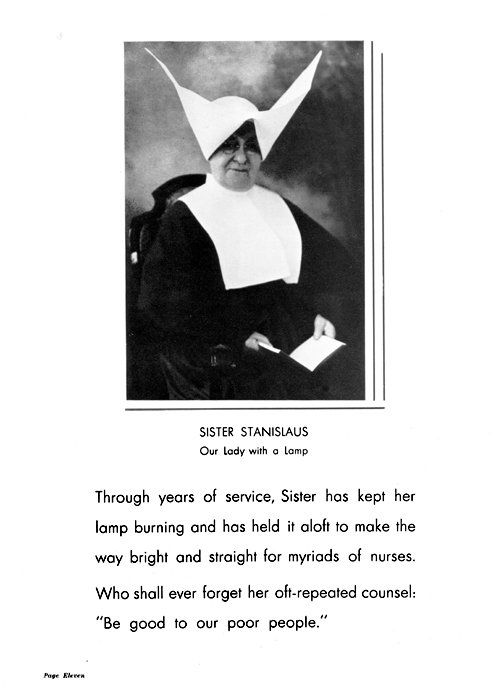

All of this is not to say that Charity has not made significant contributions to the citizens of this state. Many residents today will proudly tell you, “I am a Charity baby.” They will tell you of the Sisters of Charity who worked so diligently (free of charge) for nearly a century taking care of the poor and of dedicated doctors from both LSU and Tulane Universities in the Trauma Center fighting to save thousands of lives.

All of this is not to say that Charity has not made significant contributions to the citizens of this state. Many residents today will proudly tell you, “I am a Charity baby.” They will tell you of the Sisters of Charity who worked so diligently (free of charge) for nearly a century taking care of the poor and of dedicated doctors from both LSU and Tulane Universities in the Trauma Center fighting to save thousands of lives.

As a result of Hurricane Katrina in 2005, Charity Hospital closed its doors. It still remains standing but unoccupied. Just a few blocks away stands its replacement; University Medical Center New Orleans. The building and location are new, but its history in the Jim Crow Era should never be forgotten.

As it is often said, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

Sources: Articles are from: Salvaggio, John, M.D. New Orleans’ Charity Hospital– A Study of Physicians, Politics, Public and Poverty, LSU Press, 1992.

Durant, Thomas Jr. MD. & Roberts, Jonathan MD. A History of the Charity Hospital of Louisiana: A Study of Poverty, Politics, Public Health and the Public Interest, (pages 213-242) 2010;

The Louisiana Weekly: May 1,1926 p.1+ May 15, 1926 p.1 +May 29, 1926 + October 31,1936 p.1+ November 7, 1936 p. 1 + June 15, 1963. Photos are from: Louisiana State University Medical School Alumni Affairs files, The Louisiana Weekly.

Lolita Villavasso Cherrie

I”m a “Charity Hospital baby”, born in June of 1944. I also had my tonsils removed there. I was fortunate to remember people being kind and had no problems. Thank goodness!

I too was a Charity Hospital baby having been born on November 19, 1941.

Clearly a story that needed telling. The history of Jim Crow racism is deeply embedded in the history of New Orleans and we all need reminders of this history to prevent its repetition.

Good article.

When I taught Plane Geometry at Carver Senior High School, I used Charity Hospital as an example of the Axis of Symmetry

If you drew a vertical line down the center of Charity Hospital,

Everything on the right side would be identical on the building to the left side…thus

giving the appearance of

“Symmetry.”

It was also a 0blatant monument to segregation with

White patients on one side and Colored patients on the other…

My students got the concept clearly…

A fine example..straight to the point ..I’m sure it was not lost on your students.. We’ve certainly come a long way.. with many more miles to go to ..Blessings Brother Martinez !!!

The article defines the inhumanity of Jim Crow bigotry inherent to the dog whistle call of MAGA. Stay in the fight!

Absolutely agree

I was born in Flint Goodridge Hospital. However, I loved to hear the stories of blacks who “passed” and got jobs working at Charity Hospital. My favorite was told by an African American friend who talked of going to work at Charity Hospital and seeing someone she knew also on her way to work. She saw this person often since they arrived at about the same time. She was always careful in not recognizing the person because she didn’t want to “out” her. This reminded me so much of growing up in New Orleans and the many worlds which existed side by side which we all had to navigate.

I was born in Charity Hospital in 1949, grew up in the 1700 block of St. Bernard Ave, 1300 block of Ursuline and the 1200 block of St. Claude (now Henriette Delille). I grew up and played with people that attempted and succeeded in passe blanc (passing). I volunteered at Charity Hospital in high school and recognized several older nurses that were passing, some would speak and acknowledge my existence and some would not.

I was baptized at Corpus Christi, need I say more?

Hello Mr. Reynolds. I was born in Charity Hospital, Lived on N. Dorgenois St. in the next block from St. Aug. I too was baptized at Corpus Christi. Dr. Mims was my family’s pediatrician. I think of him often.

I now live in New York but miss home.

Thank you Ms Cherrie for your continued research for which I am pleased to get more and more history about people, places and activities in our city. I was born at home in the shadow of the Falstaff Brewery (Nat’l Brewery before the mid 40s) attended by our neighbor Dr. Mims one of our African American doctors.

Thanks Lolita for this invaluable article.I was born at Charity Hospital. Do you think it will ever be occupied again?

I am not sure, Lynn. I’m sure it will not be torn down because of its historic significance. The building is said to also be architecturally extraordinary as a art deco building from the 1920s. There has been various talks to turn it into a medical or residential facility for students at the two medical schools (LSU + Tulane) or even high-end Penthouse Apartments/shopping center. Our mayor has expressed interest in affordable housing. So as of now it is still unoccupied….Lolita

Thanks for the update!

I remember being taken to Charity’s back door when I was a child. I had broken my arm.

Dr. Mims was my husband’s grandfather. He practiced medicine in New Orleans for over 60 years. His gravesite is in Mt. Olivet Cemetery (featured in another CreoleGen article).

In the 1960’s when I was in high school I was treated at least 2 times at Charity hospital. I was treated fine but I did not know of it’s history.

I would add one correction to the story: It was Huey P. Long that convinced the Hospital to hire Blacks as Orderlies. He promised black peoples that he would get them jobs too. He used more graphic racist terms about ‘letting N——— wipe their and white people’s A—— It was not right fir white oriole to do that’. I was a Flint Goodrich baby in 1938 . 5 of my siblings were born in Charity Hospital and my first child was a Charity Hospital baby in 1960 when I was a senior at Xavier University.

I was born on the white side of Charity Hospital on 10/4/1954.

How??????

I was in my 30s or 40s when my father told me that when he came to visit my mother after the births of each kid (7 children between 1952-1960), that he would take the elevator on the white side.

I was born there on 9-9-1954. Does anyone know what floor the maternity ward was on?

The maternity ward at Charity Hospital was on the 10th floor….Lolita

I would love to recover my medical records in the archives of Charity Hospital where I was treated over a number of years when I was a child.

My late mother was a nurse there. Mom was light olive in skin tone with straight black hair of French Creole and Native American descent. She often spoke of how she and a few of her relatives were given preferential treatment over darker Blacks only because of their skin color and hair. Truth be told, from the stories she related to me, they still endured the indignities of racism…just on the other side!

As a Charity baby in 1949, I can assure my friends of color that I was only interested in the dryness of my diaper and the fullness of my tummy. It was those nutty adults who worried about the color of my nursery mates and nurses.

It’s a shame after decades that we are still living with racism. People still look the other way when wrong is being done to those that are different. We have people who say that they don’t see it. When will we become part of the Human Race and not be judged by skin color. Let’s start by changing ourselves and how we look at others. It’s not fair. Try to get to know that person and learn what’s in his or her heart, then maybe we can start to heal. Life is too short to hold so much hatred.

Born there in 1958, employed briefly 76-78 in a lab on the 11th floor. The history of it is enlightening, heart breaking and scary. When people are placed in charge and the powers that are given allows for abusive, mindless behaviors than racism can raise its ugliness. The greatness is in the history our kids and grandkids need to know.

My mother gave birth at home to four kids, in the 7th ward, with the help of a mid-wife.

My brother Ronald had his tonsils removed at Charity when he was two years old, that was in 1947, a year before I was born. His surgery was a success. My sister had a mastoid operation when she was a teenager, in the late 1950’s, that was also a success. My first experience at Charity Hospital was when my father had a stroke in 1970. My mother and I sat in the waiting room for what seemed like an eternity, finally my Dad was seen by a doctor, treated and returned home by ambulance. My father continued treatment and therapy for months, at Charity until he was able to walk with assistance. Years later my Dad had surgery, at Charity which went very well. My family received good care at Charity Hospital. I thank God for the good Doctors and Nurses who came to work to save lives, and to help people in need. It was those dedicated Doctors, Nurses and staff that made Charity a Blessing to so many people.

I am a Charity Baby! 1970

On July 9, 1953 I was my parent’s last baby born in the South and born in Charity Hospital. The sibling after me were all born in the North because my father joined the Black migration North for carpentry work in the Chicago,IL area. I was told of the medical, social and basic human injustice that had been done to African American patients and employees there even during that era. But I have this immense pride for being a Charity Hospital baby! I am so happy every time I visit NOLA and see the building! It has too much NOLA history to be demolished. History includes the good, the bad and the ugly and is the best learning tool humanity has! It would tear a part of the heart and soul out of New Orleans for the buiilding not to be there and it appears to be structurally sound. Strong enough to withstand Hurricane Katrina! Charity hospital is a testament to the evolution of human triumph over the worst of medical and social injustice. The good it over time brought about touches our souls! That is the beauty of it and the reason for these heartfelt feelings regarding Charity Hospital.

I was born at Charity Hospital in 1952. My mom had 7 babies between 1948and 1959. I remember standing in line to get a check up. It was at the back door. I worked at Charity in the early 70’s. It was a fascinating place. Charity had doctors from all over the world. I hope they decide what to do with it. It’s a very important part of New Orleans.