In early September 1963, the nation’s attention was turned in large part to the civil rights movement, in wake of the March on Washington held just days earlier. Few in the world took notice of the passing in New Orleans of Lizadie Diaz, a humble Creole woman whose life had begun nearly eight decades before in a unique cultural environment, a distinct way of life so far removed from our own. Those few dozens, who passed by her bier in Corpus Christi Church, were mostly tied to her by blood; others by neighborhood or culture. Those who assembled there for the requiem of this Creole lady represented the trinity which defined her life: family, community, and education.

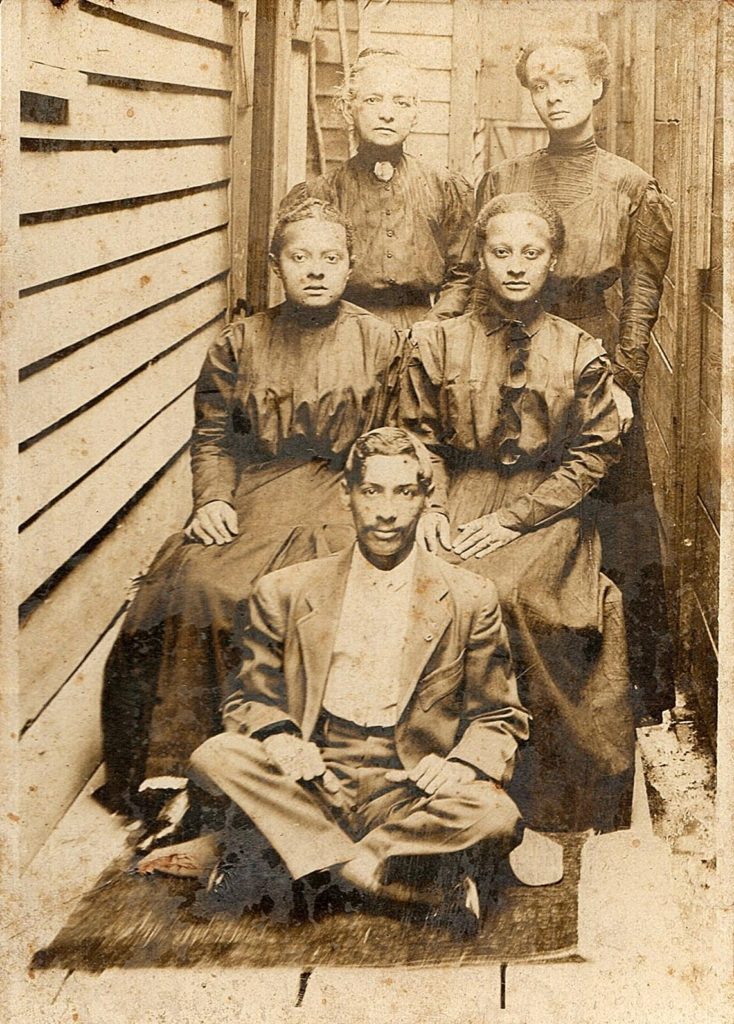

Lizadie Diaz was born, reared, and illuminated in the world of late-nineteenth-century Creole New Orleans. She was born on 11 November 1886 at what was then 208 North Claiborne Avenue, at the corner of St. Phillip. She was the fourth of five children of Domingue Firmin Diaz and Josephine D’Hollande, both natives of New Orleans who were born free before the Civil War. Lizadie grew up in a closely-knit family with her three sisters: Laura, Victoria, and Lydia and one brother, Firmin, who died at a young age. Her upbringing and historical memory were influenced by her maternal grandparents, both of whom were gens de couleur libres, including her grandmother, Marie Lizadie Colsson, for whom she was named. Like so many Creoles of that bygone era, she was given a pet name or nickname that was a shortened form of her given name. To those closest to her, she was called “Dadie.”

Standing: Josephine D’Hollande Diaz (mother); Lizadie Diaz. Seated: Lydia Diaz Sayas (sister); Laura Diaz Esteves (sister); Gentleman (Seated): Rene Sayas ( Lydia’s husband).

The family lived in the Tremé area of the city, spoke both French and English, and religiously attended Saint Augustine’s Church. Firmin Diaz worked as a shoemaker and his wife, Josephine, was a modiste. Though they did not possess much money, they did possess a rich cultural history. Both Lizadie’s maternal grandfather, Joseph Diaz, Sr., and her paternal grandfather, Joseph Florville D’Hollande, had been members of the Louisiana Native Guard.

Tragedy struck the Diaz household when her father, at the age of forty, suddenly died and left her mother to rear four little girls ranging in age from one to nine. To provide for her young family, Josephine took in sewing and trained her daughters in the profession. All of the sisters excelled at sewing and made their clothes by hand throughout their lives.

Education was valued, as it was in so many Creole families. The Diaz sisters enrolled in the Catholic Indigent Orphan Institute located at Touro and Dauphine Streets in Faubourg Marigny. Lizadie, always considered ‘brainy,’ became one of the school’s brightest scholars from the primary through the eighth grades and excelled especially in the French and English languages.

The history of the school is unique. It was founded through the generosity of an African woman, Marie Couvent (widow of Bernard Couvent) who although uneducated herself realized the importance of educating the children of her race, especially orphans. A successful property owner, Marie Couvent left a will bequeathing property she owned at Union and Greatmen Streets (now Touro and Dauphine) for the erection of a school. Madame Couvent died in 1837. It would take ten years (1847) for her dream to become a reality.

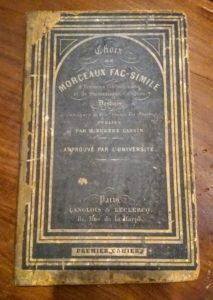

The Institute educated children of both sexes from all sections of the city and all denominations. Orphaned children attended free of charge; half-orphans, like Lizadie, paid half-tuition; and regular students paid the normal cost of tuition. It was at the Indigent Orphans’ Institute that Lizadie came under the influence of men and women who were heirs to the literary legacy of Les Cenelles, who contributed poetry and prose to newspapers, and who sought to preserve the French language. Among the instructors and directors she encountered was Madame Nathalie Populus Mello, one of the few colored Creole women of letters whose name and works survives in the historical record.

Board of Directors (1917)

Lizadie read continuously from novels and books of poetry in French. One of her favorite pastimes was attending performances, even if on a segregated basis, at the French Opera House in the Vieux Carré. She especially admired the school’s principal, Professor Paul Trévigne (1825-1907) and spoke of him often throughout her life. Trévigne had been editor of L’Union, the first newspaper published by people of color in the South. Professor Trévigne retired in July 1906. At the age of twenty, Mademoiselle Diaz applied to the school’s Board of Directors and joined the faculty in May 1907.

Lizadie’s Ivory Opera Glasses

One of five French books found in her collection, including an original copy of Nos Hommes et Notre Histoire by Rodolphe Lucien Desdunes.

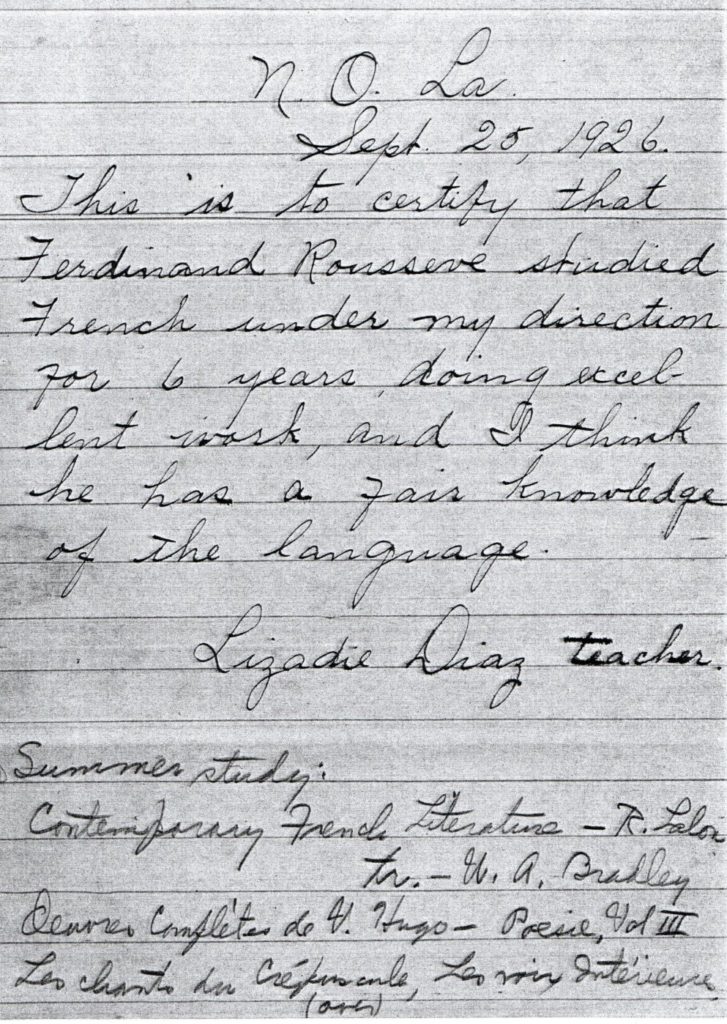

She was said by many to be an excellent teacher, fine disciplinarian, and one who had the respect of the faculty and scholars. She taught French and English to orphans as well as the children of prominent families. Among her pupils were the elder Roussève siblings, themselves, the grandchildren of the poet Lucien “Lolo” Mansion. The Roussève children went on to become a pioneering historian, priest, architect, and Professor of Art.

Although the Institute was governed by an all-male board of directors, during Lizadie’s teaching career, the faculty was led mostly by women. In 1911-1912, Lizadie served as Assistant Principal under Camille Cohen Bell (daughter of Walter L. Cohen). From 1912-1915, she held the same position under Principal Zipporah Colescott Galbreth. These women dedicated themselves tirelessly to the school, which provided them with a sphere of influence and a place of work nearly free from male control. Lizadie remained in her position until September 29, 1915, when the disastrous “1915 Hurricane” engulfed the city and completely destroyed the school building.

Catholic Indigent Orphan Institute (Dauphine & Touro Streets).

Destroyed by the Hurricane of September 29, 1915.

Classes continued for students in various other places in the neighborhood including rental property owned by the school. Determined to rebuild, the Board of Directors, teachers, and supporters walked the neighborhoods, knocked on doors, and solicited contributions from societies and businesses to assist with rebuilding. The total amount raised was $1,249.77, though it fell short of what was needed. Lizadie Diaz collected more than one-tenth of that amount herself. An appeal was made to Mother Katharine n schools, who donated the $2,000 needed for its completion.Drexel, the great benefactress of Catholic Black and India

Believed to be a photo of students attending classes at a home in the neighborhood of the destroyed school after the Hurricane of 1915.

Dedication of the new structure took place on August 1917. The headlines of the New Orleans States on August 27th read, “St. Louis School Dedicated after Rising from Ruins.” Among the distinguished speakers on the program was Lizadie Diaz, an alumna and teacher, who was chosen as the godmother of the new structure. She proudly spoke of the need to continue the work of Marie Couvent.

School opened in the newly constructed building on 10 September 1917 with the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament replacing lay teachers and with a new name for the building. The Catholic Indigent Orphan Institute which had existed for seventy years (1847-1917) was renamed the St. Louis School, at the request of Mother Katharine.

Though she left the faculty when the Blessed Sacrament Sisters took charge of the school, she very likely remained a faithful supporter and worker in the years that followed.

Throughout her life, Lizadie lived in the same household with her widowed mother and sisters. Though one by one she witnessed the marriages of her three sisters, Lizadie never married nor ever had any children. She became a revered and beloved motherly figure to her five nieces and nephews: Onelia & Paul Sayas, Alfred Leblanc, and Genard & Robert Smith. She was especially close to her younger sister’s daughter, Onelia, who showed great academic potential and whom she exposed to the classics, the French language, and various cultural activities in the city.

Lizadie with her niece, Onelia

Onelia Sayas was once asked if she knew why her Aunt ‘Dadie’ never married, especially since she was an attractive lady. Her answer was, “My aunt always told me she never married because she never found a man she thought was good enough for her.” In the period in which Lizadie was reared, girls sometimes had the luxury and the resources to pursue their educations, but boys often set about learning skilled trades or working after the lower grades.

After leaving the teaching profession, Lizadie began a career she had been prepared to undertake since a young girl. She became a “tailoress,” as she was regularly described, with the National Tailoring Company. Sewing was always considered a very acceptable and honorable form of employment at that time for women and one she was very qualified to do. Those older generations of Creoles valued the use of the intellect and the mastery of skilled professions, which gave one a merit that transcended the color line and allowed one to work for oneself should the need arise. In addition to her professional work, Lizadie made childhood clothes and First Communion outfits for her nieces and nephews.

Sewing was just one multigenerational legacy among the women in Lizadie’s family. Her mother, aunt, and other female relatives were members of the Sainte-Hélène Société d’Assistance Mutuelle (Saint Hélène Mutual Aid Society). This all-female society provided the services of a doctor, druggist, and a society tomb in St. Louis Cemetery No. 2 to its members. While collecting money for the rebuilding of the Indigent Orphans Institute, Lizadie remitted $25.00 from the Sainte-Hélène Society alone. She quite likely joined her female relatives in the society, which transacted its business in French as late the 1940s.

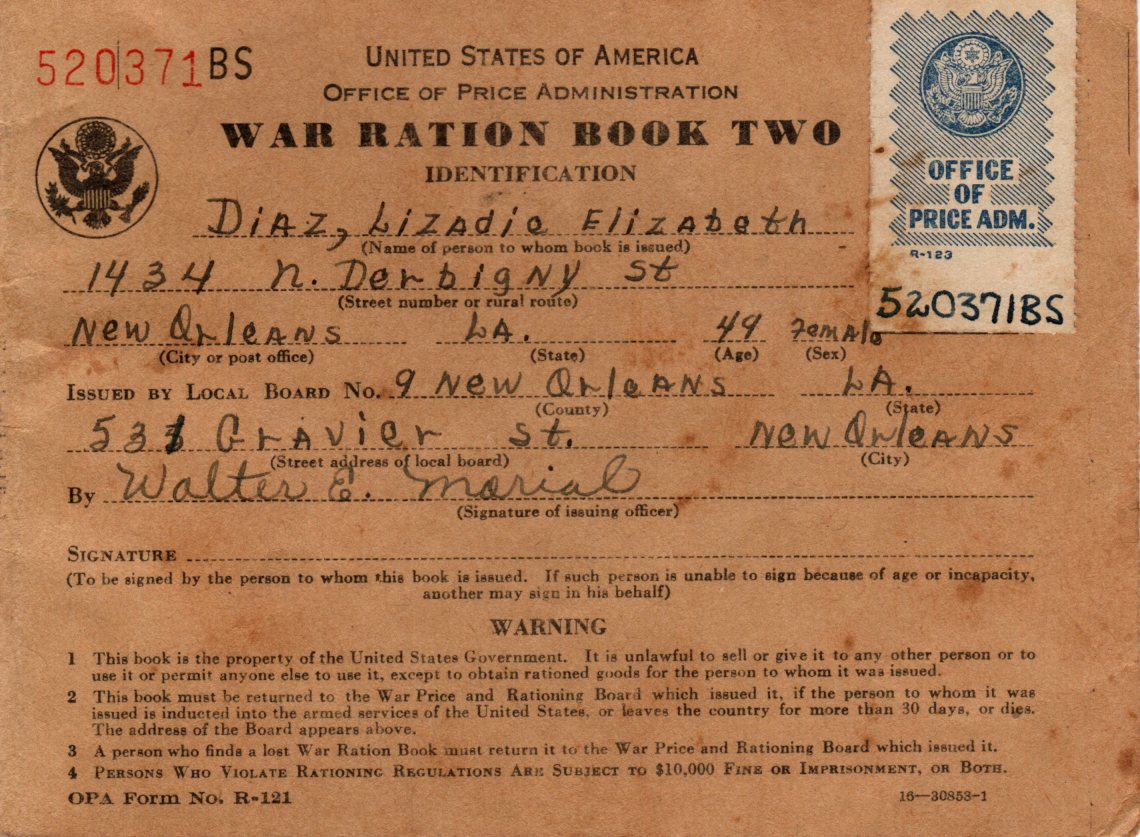

Along with a precious few of her old volumes of French poetry and ‘readers’ and a pair of nineteenth-century ivory opera glasses, some of the surviving artifacts of Lizadie’s life include her ration books from World War II. As she approached her senior years, she survived the Great Depression and witnessed the changes brought about by World War II. As so many young people from her community went off to the military service or found work in the war production industries, they expanded their world view beyond New Orleans and in many cases made lives for themselves beyond the segregated South.

With the passage of time, ‘Dadie,’ saw her world grow smaller and smaller. Her three beloved sisters all predeceased her – Victoria Diaz LeBlanc in 1910; Laura Diaz Esteves in 1930, and Lydia Diaz Sayas in 1957. Only Lizadie would live long enough to come close in age to her octogenarian mother, and her old unmarried aunts, who all died in their eighties.

One wonders if the protests for civil rights in the 1950s and 1960s awakened in her memories shared by her aged professor Paul Trévigne, who himself had made journalistic contributions to the civil rights movement of a century before. As she entered her eighth decade of life, fewer and fewer people spoke her mother tongue, French. In 1919, the French Opera House, so loved by the Creole population regardless of race, burned to the ground. In 1956, the St. Louis School of Holy Redeemer Parish, which she christened as ‘godmother’ was razed to make way for a modern three-story building. By 1969, the very home where she was born was demolished to make way for a down ramp of the Claiborne Avenue overpass. Over time, nearly every unique aspect of the trinity that defined her life – family, community, and education – eroded away.

One wishes for the opportunity to have interviewed this unassuming yet highly-cultured grande dame. Fortunately, her memory was kept alive by her loving nieces and nephews who fondly recalled her as a warm yet stately grandmotherly figure with her French books, her refined manners, and her finely sewn clothes. Mademoiselle Lizadie Diaz died on 3 September 1963 at the age of seventy-seven years old. After her requiem Mass in Corpus Christi Church, she was laid to rest with her mother and sisters in a wall vault of the Saint Louis Cemetery No. 3. We render our respect to this scholar, teacher, modiste, and ‘Tante’ extraordinaire.

Sources: All photographs above are from the personal collection of Lizadie Diaz, which became the possessions of her niece, Onelia Sayas Cherrie. Special thanks to Edward Cherrie for sharing with me so much of his memories and artifacts of his great aunt.

Other Sources: New Orleans States, “St. Louis School Dedicated after Rising from Ruins” 27 August 1917 p. 3; Amistad Research Center, “History of the Catholic Indigent Orphans Institute,” published by Board of Directors (1917); Interviews with Onelia Sayas Cherrie by the author in 2005.

Thanks, Jari Honora for assisting with helping to tell this story.

Lolita Villavasso Cherrie

Thanks Ms Cherrie!! Your historical research is wonderful and fascinating. One never stops learning and I haven’t, thanks to you. I look forward to more.

WOW! It is so refreshing to be able to read about the history of family and friends from many, many years ago. We don’t always realize how important it is to preserve our ancestry through articles and pictures of who they were and the contributions they made to society. We are so fortunate in this day and age to be able to keep our own records through technology and especially through the love and dedication of people like Lolita Villavasso Cherrie, and the people who assist her in researching and providing this valuable information to us. Thank you, Lolita, for keeping our families informed and educated about the history of our culture. – Patricia Braud Bishop

Loved the article. Numa Rousseve (we called him ‘Prof’) was head of the art department at Xavier Univ when I was an art student there.

What a lovely portrait of a great lady. Thanks, Lolita and Jari. Great work as always. I was happy to see my grandfather Barthèlmy Abel Rousseve among the board of directors in 1917. He was my father’s father. He died before I was born. Also to see the note about my uncle Ferdinand and his progress ln learning French.

I truly enjoyed reading this story. I am also the great grand daughter of one of the BOARD OF DIRECTORS, which is included in the history. George Doyle was my paternal grandmother’s father. He was also one of five men of color who was a policeman in New Orleans. He was appointed by President Howard Taft as a United States Federal Marshal. What wonderful contributions have been made to the City of New Orleans by the Creole Community. I am very proud to stem from such greatness. Lizadie Diaz was a woman before her time and has left a positive mark and legacy to the history of New Orleans.

Thank you for sharing this amazing story. I enjoyed hearing the familiar New Orleans names like “Cherrie” and “Rousseve”. I loved hearing that St. Katherine Drexel provided funds to rebuilding the school destroyed in 1915. Keep up the good work.

Thank you for sharing this story. Paul Trevigne was my mother’s great grandfather. If you have any pictures of him I would appreciate you sharing it with me. I have a picture of my great grand mother. Her name is Marie Trevigne.

Unfortunately, there are no known photos of Professor Paul Trevigne. Many researchers have and continue to search, but none have been proven to exist…Lolita

George Doyle is also one of my ancestors, as well.

Thank you, Lolita and Jari for this wonderful story. You make history come alive.

I really enjoyed the article. I graduated from Holy Redeemer in 1957. My siblings attended, also.

Learning about the history of Holy Redeemer was a great lesson for me.

Excellent ties w/Marie Couvent

Lizadie Diaz was an admirable woman, very inspirational!. Lolita and Jari, thank you for including the accompanying photos and documents. They made the story very much alive!

Thank you so much for this fascinating article! The family photographs and the pictures of Lizadie’s possessions add so much. Her dress in the group photo of her family certainly shows how skillful she was in sewing her clothing, and I love the skirt she’s wearing in the photo with Onelia!

Thank-you Lolita and Jari!

Loved it.

Thank you for sharing Lizadie’s story.

I pray that they find a picture of him one day. Thank you for responding back.