Through our articles on CreoleGen, we have explored the lives of many women – wives, mothers, educators, civic leaders, artists, professionals, religious sisters, antebellum femmes de couleur libres, etc. We have sought to give them recognition and present their stories as best we could with the surviving historical record. Most of these women lived in the nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries, they occupied a precarious place at the intersection of race and gender. They lived in times when making a living and just living were experiences circumscribed by the limitations put upon them as people of color and as women. We present here the story of a young woman who found work, love, violence, infamy, and a few scribbles in the historical record on the seedier side of New Orleans.

Florestine Breaux – 1912

Florestine Breaux’s name appeared in the local papers at least nine times between 1910 and 1922. The notoriety she achieved in her short life of thirty-six years came from her many run-ins with the law. Florestine lived and worked for at least thirteen years in Storyville or the nearby “Black Storyville,” both legally designated prostitution districts created by “reformer” city councilmen in 1897 as a way to contain and curtail the “world’s oldest profession.” Florestine Breaux was a prostitute in New Orleans’ famed “Red Light District.”

Florestine Breaux was born on 14 September 1886 in rural Saint James Parish, Louisiana, about sixty-five miles upriver from New Orleans. Her father was Théophile Braud, who had been a free man of color before the Civil War, and who worked as a cigarmaker and ferryman. Florestine’s mother, Flora Richardson, born about 1856, was likely the daughter of freedmen, also from Saint James Parish. Florestine was baptized “Marie-Florestile [sic] Breaux” on 5 February 1887 at Saint James Catholic Church. Her godparents were Télesphore LeBlanc and Marie Jacob.

Florestine’s parents were not married though they had at least five children (Theophile, John-Norman, Joseph-Wilton, Marie-Florestine, Marie-Aliska [Alice]) between roughly 1880 and 1888. In the 1890s, Théophile went on to have at least two more children with a woman named Emily Martin, to whom he was also not married. Florestine likely never experienced a typical home life. The upbringing of Florestine and her siblings seems to have been left to her uncle and aunt, Isaiah Richardson and Matilda Boyd.

Throughout the Red-Light District’s history, there were guidebooks published annually, listing the names, addresses, and races of the women who worked there. The earliest of these “blue books,” as they were labeled, to include Florestine Breaux was published in 1909. She was listed that year as residing at 1520 Bienville Street. Each of the addresses found for her – 1410 Bienville (1910, 1913), 1526 Bienville (1912), and 127 North Villeré (1919), was in the District, with the exception of 425 South Liberty (1915), which was across Canal Street in what is called “Black Storyville”; and her last-known location, Bienville and Tonti streets, which was about eight blocks from the back of the District.

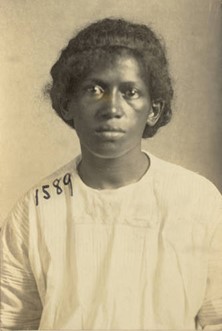

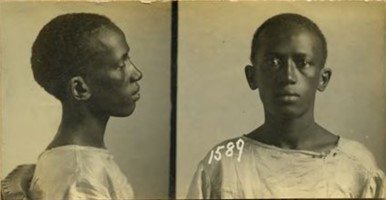

Florestine stood about 5 feet 2 inches tall and kept a constant weight of about 100 pounds. She was slight of build, with dark brown skin; ‘kinky’ black hair, over which she wore false hair; and two gold upper teeth. The scar across the center of her forehead may have been the remnant of a tussle she engaged in while living and working in the District. She was consistently identified as a “negress” a word that like its counterparts – mulatress, quadroon, octoroon, etc. – encapsulated her race, complexion, and gender all-in-one.

Florestine Breaux 1912

It is important to remember that prostitution itself was legal in Storyville, in fact it was its raison d’être, a place where it could be permitted yet controlled. The run-ins with the law that the working women and their customers had were related to all manner of other criminal activity – thefts, assault, drug charges, murder, and even being ‘suspicious persons.’ Florestine’s first known arrest was in October 1910, when she was arrested for selling cocaine in an undercover operation carried out by two police detectives. They approached a “woman in the Red-light District” named Josephine Johnson and gave her a dollar to find them some cocaine. She readily directed them to Florestine Breaux’s place, where Josephine presented Florestine with the dollar and received a “package which contained about 25 cents worth of the stuff.” Florestine was arrested and in the course of questioning, a “well-known dentist” Dr. Sayre B. Knapp was indicated and arrested as furnishing the prescription for the drug.

Florestine’s next arrest came on 12 August 1912, when she was taken in for petty larceny. Petty larceny would prove to be Florestine’s most consistent crime. On that occasion, Florestine was thoroughly described and photographed on both a mugshot card and Bertillon card by the Police Department. There are approximately 1,600 mugshot cards and approximately 700 Bertillon cards in the records of the Police Department in the City Archives at the New Orleans Main Library. For these records, Florestine was pictured both with and without her false hair.

Six months later, on 17 February 1913, Florestine Breaux (1410 Bienville), Jennie Garnier (1511 Bienville), and Pearl Smith (1542 Bienville) were all arrested for fighting with Louise Raymond (1542 Bienville) in what was described as “one of the most vicious hand-to-hand battles the police have ever seen fought in a neighborhood where such disturbances are frequent.” One of Louise Raymond’s eyes came completely out of its socket when she was hit with a brick. She was taken to Charity Hospital while her three co-combatants were taken to the Fourth Precinct and charged with “assault, beating, and wounding.” – While tales of Josie Arlington’s Basin Street palace and Lulu White’s luxurious Mahogany Hall may be legendary, stories like these were far more common and reflect life for the many unfortunate women who occupied the ‘cribs’ in the District as their places were called.

In October 1913, Joseph Jackson, who had formerly been a deputy sheriff in Bogalusa, Louisiana, was arrested after drinking “a good deal.” He was loaded into the patrol wagon with Florestine, a “negress of the Red-light District,” and several other black women. Florestine, who The Daily Picayune described as “quite quick with her fingers,” was accused of stealing $200 from him while he was inebriated. At least ten witnesses were found who claimed that soon thereafter Florestine was observed breaking several “big bills.” She was subsequently arrested for theft.

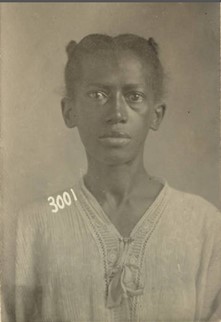

Florestine Breaux – 1920

In at least five other instances (1915, 1916, 1917, 1919, and 1922), Florestine was noted in the newspaper in connection with theft, and in particular with shoplifting. In May 1922, the floorwalker at Kress Department Store, who knew Florestine for her “taking ways,” had her arrested for stealing twelve silk dresses and at least a dozen pairs of white men’s socks. Three days before Christmas in 1915, she was arrested at the Krauss Store for stealing a suit of men’s clothes, several pairs of silk stockings, and pieces of jewelry. Other stolen merchandise was found in her home at 425 South Liberty Street, where detectives also found Joseph Doherty and a vial of morphine and hypodermic needles.

Joseph “Pinky” Doherty had a pretty colorful history with the police in his own right, including 16 February 1916, when on that early Wednesday morning, he was arrested for the burglary of three drug stores and a saloon, in the company of Florestine Breaux, “with whom he [was] said to be ‘friendly.’” There is little doubt that the initials “P. D.” and the heart which Florestine had tattooed on her left arm from at least 1912 forward, was a sign of her affection for “Pinky” Doherty.

On 26 October 1919, Florestine was arrested with several other black women described as “an organized gang of Negro shop lifters which has been operating extensively in Canal Street department stores.” She was sentenced to a minimum of fifteen months and a maximum of two years in the Louisiana State Penitentiary on 5 December 1919. At the time, she lived at 127 North Villeré Street. She arrived at Angola on 27 January 1920 and was discharged on 27 July 1921, after serving eighteen months.

Either prison did not have a reformative effect, or necessity or ‘habit’ dictated that she return to stealing again. As noted, she was arrested at least one more time in May 1922 for shoplifting from the Kress Store.

Florestine Breaux died of syphilis in Charity Hospital on 13 December 1922, when she was just thirty-six years old. Her four brothers all had families and died in their late 60s, 70s, or even 90s, in the case of her half-brother, McGary Breaux. Her half-sister, Marie-Nancy Breaux Robinson, lived to be about 77 years old and was married for over forty years. Unlike her two younger half-siblings, who had a mother who was present, Florestine and her four full siblings, were reared by relatives who already had families for which to care. She was also a woman, and without a skilled trade or common labor like her brothers, her options were limited outside of the domestic sphere. She left no personal statements or testimony that give insight into her life, but hopefully, this brief reconstruction of her life sheds light on the experience of the lesser-known women who lived and worked in New Orleans’ Storyville District.

Jari Honora

Sources:

“Dentist Arrested for Selling Cocaine, Though He Claims Her a Patient,” The Daily Picayune, 25 October 1910, p. 7, col. 6; “Second City Criminal Court,” The Daily Picayune, 14 August 1912, p. 4, col. 4-5; “Negress Loses an Eye in Hand-to-Hand Fight,” The Times-Democrat, 18 February 1913, p. 5, col. 6; “Relieved of $200: Joseph Jackson, of Bogalusa, Was Robbed in District,” The Daily-Picayune, 13 October 1913, p. 7, col. 2; “Alleged Shoplifter Caught,” The Times-Picayune, 23 December 1915, p. 15, col. 2; “Four Burglaries Tuesday Night,” The New Orleans Item, 16 February 1916, p. 4, col. 5; “Negress Gets Long Sentence for Theft,” The New Orleans Item, 24 April 1917, p. 2, col. 3; “Gang of Negro Shoplifters Broke Up,” The New Orleans Item, 26 October 1919, p. 16, col. 3; “Negress Caught in Store Charged with Shoplifting,” The New Orleans Item, 11 May 1922, p. 15, col. 2.

“Theophile Breaux [Jr.],” obituary, The Times-Picayune (New Orleans, Louisiana), 23 July 1946, p. 2, col. 6; “Wilton Breaux,” obituary, The Times-Picayune, 17 June 1951, p. 11, col. 5; “John Norman Breaux,” obituary, The Times-Picayune, 7 December 1958, p. 18, col. 2; “Marie Nancy Robinson,” obituary, The Times-Picayune, 25 December 1974, p. 16, col. 6.

Diocese of Baton Rouge Department of Archives, Diocese of Baton Rouge Catholic Church Records (1886-1888) Volume 17 (Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Catholic Diocese of Baton Rouge, 1997), 102, entry for Marie-Florestile Breaux, baptized 5 February 1887; citing St. James Church (St. James) Book 20, p. 112. – For Florestine’s siblings’ baptisms, see John Breaud, Volume 15, 105; Joseph-Wilton Breaux, Volume 16, 96; Marie-Aliska [Alice] Braud, Volume 17, 102.

1900 U.S. census, Ascension Parish, Louisiana, population schedule, Police Jury Ward 5, p. 305 (stamped), enumeration district (ED) 8, sheet 21-B, dwelling 502, family 550, line 53, Florestine Braux; digital image, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed 20 May 2021); citing Family History Library film 009691, roll 135. Theophile, Florestine, and Alice Braux [Breaux] are enumerated in the Isaac [Isaiah] Richard[son] household as nieces and nephews.

Louisiana State Penitentiary, Convict Records 18 (nos. 9901-12855) (1916-1921): no. 12340, Florestine Breaux, 27 January 1920; digital image, “Louisiana State Penitentiary Records, 1866-1963,” FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org : accessed 20 May 2021), path: Correctional institution records > Convict records vol 18 no 9901-12855 1916-1921 > images 240-241 of 311.

New Orleans Police Department, Mugshot Collection: mugshot B46, Florestine Breaux, 15 August 1912, NOPD number 1589; digital image, “New Orleans Police Department Mugshot Collection,” New Orleans Public Library City Archives & Special Collections (https://archives-nolalibrary.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/ : accessed 20 May 2021), path: New Orleans Police Department Mugshot Collection > Browse > Breaux, Florestine. There are three copies of the same mugshot and information card labeled B46, B59, and B124.

New Orleans Police Department, Mugshot Collection: mugshot B60, Florestine Breaud, 14 January 1920, NOPD number 3001; digital image, “New Orleans Police Department Mugshot Collection,” New Orleans Public Library City Archives & Special Collections (https://archives-nolalibrary.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/ : accessed 20 May 2021), path: New Orleans Police Department Mugshot Collection > Browse > Breaud, Florestine.

New Orleans Police Department, Bertillon Card Collection: Bertillon card B37, Florestine Breaux, 12 August 1912, NOPD number 1589; digital image, “New Orleans Police Department Bertillon Card Collection,” New Orleans Public Library City Archives & Special Collections (https://archives-nolalibrary.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/ : accessed 20 May 2021), path: New Orleans Police Department Bertillon Card Collection > Browse > Breaux, Florestine.

1920 U.S. census, Orleans Parish, Louisiana, population schedule, New Orleans Ward 3, p. 305 (stamped), ED 36, sheet 3-A, Parish Prison, line 9, Florentine Burgus [Florestine Breaux]; digital image, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed 20 May 2021); citing Family History Library film 009691, roll 135. The transcribed name is completely incorrect.

Orleans Parish, Louisiana, Death Records, volume 185, page 1199 (1922), Floristine Breaux [Florestine Breaux]; Louisiana State Archives, Baton Rouge.

Emily Landau, “Storyville,” 64 Parishes, online encyclopedia, Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities (https://64parishes.org/ : accessed 20 May 2021).

Thanks for sharing this interesting article.

She has my deepest sympathy for having known only a life so hard lived. Thank you Jari. You always bring well researched articles.

Thank you for your research on this topic and era

My grandfather was Theophile Breaux. I believe this was his sister.

What a great and thoroughly researched story. I would love to read about more of these prostitutes stories.

One does not know what one has to go through, unless one could walk in ones shoes. Thanks for sharing this interesting article about a woman who grew up having to live a rough life to survive in New Orleans, during the Jim Crow south.

Wow, a true story of survival! She never had a chance for life!

Thanks for sharing a woman of color’s perilous

real life journey during this era of Louisiana history.

Thank you for this article, so much sad history to be told and unfolded.

My sympathy goes to Florestine Breaux for the hard life that she lived. In 1910, my great grandfather, the Rev. Peter Clark, pastored Union Chapel Methodist Episcopal Church on Marais St. and Bienville.in Storyville. The church might have offered women in the District some solace, and there was a legal fight for the church to remain there after Storyville was established. However, in 1914, city police barred all the children of Union Chapel from attending Sunday school. Children found in the district could be taken from their parents and placed in public care. With no way to accommodate children, Union Chapel closed permanently. .

Beautifully researched and presented. Thank you.

I have much sympathy for Florestine Breaux, life was very hard for these people especially the black women. It was harder for them for being abused. I hope she finds her peace with God, and may she RIP.

I love the detail about her tattoo with the initials and the heart. It is a glimpse of love in a short, difficult life.

This article was well written. It reads like a journal and a history book. Thank you Jari

Thank you, my brother, for sharing the details of how difficult it was for oppressed cultures to survive within an area that profited from the abuse of our people. This is yet another account of the will and determination of our people to survive, although, the consequences were known to the victims of these abusive tactics. No matter the consequences our people continue to survive under this oppression.

It’s the grace of our creator that continues to enable us within a system that profits from our demise. These stories provide understanding of our current situations of injustice and purposeful intimidation for those that profit from our struggles.

Such an interesting and detailed story about the struggles of this woman who only did what she had to do to survive…. she suffered and lived her hell on earth…. I hope that she was able to find some joy and comfort somewhere during her lifetime . Her story touches my heart and it tells me that even the smallest act of kindness, such as a smile, can give someone a glimmer of light and love…Rest in Peace Florestine Breaux …..

What a very sad commentary on man’s inhumanity to man. Rest in Peace Florestine Breaux.

Very interesting article. I’m wondering if she is related to Jazz musician Wellman Braud of Welcome-

St. James, LA?