“Epidemic of Bombing”: Residential Segregation in New Orleans (1924-1927)

The “Roaring Twenties” are remembered as a decade of hot Jazz, smuggled alcohol, fun, and peace, coming on the heels of the First World War and just before the Great Depression and World War II. It was also a time of population growth as the composition of neighborhoods changed, families grew, and more and more people migrated from the rural parishes into New Orleans. White families in many sections of the city, but particularly Uptown, resented the black homeowners who purchased property in previously all white sections. They were determined to maintain residential segregation. They tried first through legal means – which was haphazardly enforced – but soon resorted to detonating bombs at Black homes and businesses as a form of intimidation.

On Tuesday, 16 September 1924, it took the City Commission just ten seconds to adopt Ordinance No. 8037 which made it illegal for the city engineer to issue a building permit to a Negro seeking to build in a “white community” or a white person seeking to build in a “Negro community” without the written consent of the majority of the people of the opposite race. Another section of the ordinance made it illegal for anyone to set up residence – that is rent or own – in a section inhabited by a majority of the opposite race. The penalty was a fine of up to $25, imprisonment for up to 30 days, or both. The local ordinance was in keeping with similar state legislation, Act No. 118, which was introduced by State Senator Thomas A. McConnell of New Orleans and became law in July 1924. Following the Commission’s vote there was thunderous applause and Mrs. Mary Robertson Stephens, a white homemaker, addressed the body saying, “You may be sure, that not only myself, but every other mother of white children in New Orleans sincerely appreciates this restriction that will prevent Negro children from coming into our communities and mixing with our children.”

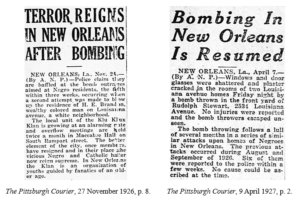

The city ordinance was passed on a Tuesday and by the week’s end, The Times-Picayune already reported the appearance of red and white signs reading: “Under the new law – Act 118 of 1924 – this block is for white only anyone destroying this sign will be dealt with according to law.” Between the passage of the ordinance in 1924 and 1927, several arrests of Black homeowners were made and at least a half-dozen bombs were set off. Each time, the bombing incidents were reported largely as childish stunts in the mainstream press or covered matter-of-factly in the Black press with little to no outcry for justice.

The young educator and fiery editor of The Louisiana Weekly, O.C.W. Taylor. upgraded the black community to push for serious investigations and possibly to rectify the matter themselves. Taylor noted that while New Orleans had “for such a long time been regarded as the most cosmopolitan city of the South and probably the city of the South most devoid of racial animosities and evident prejudices,” it had “for the past few weeks been shaken with a series of bombing outrages which has been traced directly to attempts on the part of white citizens to intimidate Negro residents in a section of the city where Negro residents seem to be not wanted.”

One of the first cases to emerge under the new law was that of Ms. Anna M. Beck, a teacher at Thomy Lafon School, who was arrested in October 1924 for moving into 3421 Milan Street in what was considered as white neighborhood. There were high hopes on the part of the local branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) that Mrs. Beck’s incident would be a test case to put the legality of the ordinance before the courts. The NAACP branch was led throughout this decade by physician Dr. George Washington Lucas. The NAACP hired two local white attorneys, Loys Charbonnet and Fernand F. Teissier, as well as the well-known Black attorney Frank B. Smith to argue the case. Dr. Lucas ultimately decided that Mrs. Beck’s would not be the case to pursue – there was the very real chance that should she surrender bail, she would remain in jail for several days and that the whole affair would cause the School Board to dismiss her from her teaching position.

That same month, Joseph W. Tyler, a white property owner at Magazine and Walnut streets obtained an injunction to keep Benjamin Harmon, the Black man who owned a single cottage at 232 Audubon Street from converting it into a double home to rent to Negroes. Mr. Tyler’s attorneys argued that the city ordinance and the legislative act prohibited this because Mr. Harmon did not obtain the consent of his white neighbors. The case met with initial success in the Civil District Court, where Judge Hugh C. Cage ruled that the ordinance was unconstitutional. While opposed to the law, Judge Cage agreed with its intent, saying “Race prejudice in Louisiana is as concrete a fact as caste is in India … This is a condition not a theory.” On 2 March 1925, the State Supreme Court overturned the ruling, which destined the case for the United States Supreme Court.

In the wake of the State Supreme Court’s decision, on 4 March 1925, Mrs. Pearl Frederick Dejoie of 2708 Cadiz Street, was arrested on a charge of interfering with an officer. Mrs. Dejoie, the wife of Prudhomme Dejoie, secured a permit from the city engineer’s office to build a new home at 3424-26 Delachaise Street, but failed to state it was to be used for Negroes. Residents of the neighborhood complained to the city engineering department and police ordered the building halted. Mrs. Dejoie objected to the orders of the police and was arrested.

The fate of Mrs. Dejoie, Mrs. Beck, and other Black property owners and residents remained in limbo as the community raised funds to bring the Harmon test case before the Supreme Court. In the meantime, unskilled novices sought to intimidate Negro residents by detonating bombs. According to the papers, in previous years, it had been the custom of white hoodlums to pass in automobiles and pelt Black citizens with rotten fruit, stones, etc. The continual use of dynamite escalated the situation to a much more dangerous level.

The earliest recorded explosion after the passage of the residential segregation act took place on Saturday, 30 October 1926, at 11:00 p.m. Its target was the newly built Lincoln Theatre located at the corner of LaSalle and Louisiana Avenue. Luckily, it missed its target and landed in a garbage dump adjoining the theatre. No one was harmed and very little damage was done. No reason was given other than it was the work of vandals who were intent upon intimidating Negroes who owned property in Uptown New Orleans.

The second explosion on Monday, 1 November 1926, was heard for more than a mile and was detonated at the home of Mr. Henry English Braden, Sr. Mr. Braden was the successful owner of the Astoria Hotel and Restaurant at 237 South Rampart Street and president of the Douglas Life Insurance Company. He had only recently finished construction of his palatial home at 200 Louisiana Avenue at the corner of Danneel Street. As the Braden family slept in the rear of their home, they were awakened suddenly by the sound of a large explosion.

Mr. Braden arrived home shortly after midnight, surveyed the damage, and called the police. The bomb exploded in front of the home on the concrete steps leading up to the front door but caused mostly cosmetic damage. Similar damage was also done across the street to the rectory and newly built Holy Ghost Church.

Barely two weeks later, a second bomb exploded on 14 November at Mr. Braden’s home. As the terrace exploded and large holes were torn in the ground, eyewitnesses in the area noticed an Essex car as it sped past the home. Luckily, a passer-by copied the number on the license plate and turned it over to the police. An investigation revealed that the license was issued to a man in Selma, Louisiana. The man was never apprehended. Many believed the police never investigated the matter.

Mr. Henry English Braden, Sr., grandfather of Dr. Henry E. Braden III & great-grandfather of Senator Henry E. Braden IV

The bombings continued into the following year, 1927, especially during the months of March and April. George W. Washington’s property at 2532-34 Louisiana Avenue was targeted not once but twice, once on Friday, 25 March at 8:30 p.m. and again on Sunday, 27 March at 8:00 p.m. No one was injured but the explosion tore large holes in the ground and shattered all the windows on both sides of the house.

At the time of the second bombing, the police were called out, but witnesses claim they were not at the scene during the time of the bombing. Mrs. Rudolph Stewart (who with her husband and daughter) occupied the other apartment in the home, was thrown from her seat by the force of the explosion. It was reported that several shots were fired at the bombers, but no injuries were reported.

On the night of 10 April 1927, the amateur dynamiters struck again. Mr. Pinkey Southall discovered three sticks of dynamite, wrapped in fuse wire under his house. One end of the wire was charred, and it was evident a match had been applied but the fire in the fuse was extinguished before it had made much headway. The explosives were later thrown into the river.

In 1927, Harmon v. Tyler was finally heard by the United States Supreme Court. The high court ruled on 14 March 1927 that the city ordinance and state act violated the 14th Amendment to the Constitution in that Mr. Harmon would be deprived of his property without due process, and that he would be deprived of the right to lease his property to a constitutional or qualified person on the sole ground of race or color.

Despite the judicial victory, sporadic bombings continued into the 1930s. Even as late as the 1950s and 60s, the arrival of a black family into a previously all-white block was met almost overnight with the appearance of “For Sale” signs on the adjacent properties. Even though schools and public accommodations remain legally segregated, these largely working and middle-class White residents overall could not fathom living in close proximity to Blacks, many of whom shared the same ambitions, ethics, and way of life as they did. This “White Flight” from the city began following the failure of discriminatory laws and vigilante bombings keep black homeowners and residents out in the 1920s. It played a huge role in the growth of Metairie, Kenner, the Northshore, and other suburban communities. The “epidemic of bombing” was just symptomatic of the debilitating illness of racial prejudice.

Lolita Villavasso Cherrie & Jari C. Honora

Sources: The Louisiana Weekly, 20 February 1926, 2 April 1927; 16 April 1927; 20 February 1926, 6 November 1926, 20 November 1926, 19 March 1927, 2 April 1927, 16 April 1927, 17 April 1928; The Pittsburgh Courier, 13 November 1926, p.1; The Times-Picayune, 19 September 1924, p. 1, 9; 29 May 1925, p. 29; 15 November 1926, p. 2; The New Orleans Item, 30 October 1924, p. 1-2; 2 March 1925, p. 10; 5 March 1925 p.5; The Black Dispatch, 09 December 1926 p.2; Shannon Frystak, Our Minds on Freedom: Women and the Struggle for Black Equality in Louisiana, 1924-1967 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2009), 12-13.

I will mail this to relatives of Henry Braden including my daughter, Megan Braden Perry.

Wonderful article! Now I understand the significance of living on Louisiana Ave. and why it was spoken of with what seemed like awe when we visited friends on that Ave. None of this was spoken of during my childhood even though my aunt Pearl was one of the women arrested, as stated in the article. Our family was living in Gentilly by the time I became a member so perhaps they simply wanted to put this behind them.

Thanks to the authors, Cherrie and Honora, for their research and to Creole Gen. for publishing it.

Hi Linda, would you happen to have a picture of your Aunt Pearl? I would love to include it in our story since all our photos are of men only. If not, maybe you can put me in touch with another relative who may have one. You can reach me at 5044535922 or Lolitac454@aol.com

All my family photos were lost in Katrina, sorry. Her granddaughter, Michelle LaPlace Watts, may be able to help you. I don’t have an email address for her but I do have a phone number. Michelle’s info should be available to Creolegen because that’s how we reconnected a few years ago after an article was done on Papa, Dr. Fredericks’, so search for her email address using their records or let me know if you would like her phone number.

For many years now we Creoles and black people have been moving to the suburbs to get away from the serious crime problem, just like the white Creoles did in the past. So I believe it is safe to say that this can be called Creole and black flight as well. Thank you.

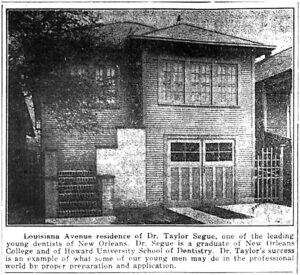

I am the grandson of Dr. Taylor Segue and am trying to locate a letter he wrote to the New Orleans Mayor about the limited housing choices of black New Orleanians due to racial discrimination, he apparently also addressed the inability of blacks to play golf on Louisiana’s public golf courses. This letter and its hate filled response came to the attention of Jewish philanthropist Edgar B Stern and his wife Edith and is rumored to be a catalyst for their involvement in the Pontchartrain Park housing development and the development of the Joseph M Bartholemew golf course. Are you familiar with this letter, and if so, can you share a copy of the letter and response with me?

Greetings Mr. Segue:

My maiden name is Joy Sigur. your last name Segue came along a time when my grandfather was changing his last name to suit the people because they had such difficulty saying his last name.

Have you any history on your last name.

My grandfather’s name was

Originally ??

but in the early 1900’s

Segue

Segur

Sigur

In the 40’s and 50’s we were the only Sigurs. Now there is a boat load.

Peace and Love! Thanks, if you can lend any light on that I would appreciate it.

Joy Sigur

Try the Amistad Research Center at Tulane University, they may have a copy or can assist you in finding one. I believe Long Vue House and Gardens also has a collection as well as staff that may be able to help. There is also the Historic New Orleans Collection, a museum that preserves old documents, photos, etc. HNOC’s websites will help you in directing your inquiry or the authors of this article may have better answers to your question. Good luck.

Thank you so much for posting this article. I save all of the articles from CreoleGen and always look forward to receiving them. It is such a beautiful way to learn about the neighborhood you grew up in and being able to see proof of its history in writings and pictures. I am always extra excited when I see the names included about my own dear family’s history. Dr. Rivers Frederick, the father of Pearl Frederick Dejoie, was my mother’s cousin. I was born in 1942 and we lived uptown on Liberty Street but I remember going to my cousin Pearl’s house when she lived in Gentilly many times. There are so many things I never knew about the sacrifices our families went through in those years to try to fight for equality for all. We’ve come a long way since then, but we still have far to go to reach that “equal rights for all” place in this country. I feel that God, prayers and our love for all of our neighbors will get us there one day. God Bless us all.

Thank you for this erudite article about another dark era in these yet to be united states of America. I am grateful for those forefathers who exhibited the stamina and fortitude required to meet the challenge !!!