After the Thanksgiving feasts have ended, attention turns to football and marching band rivalries as the city of New Orleans fills with devoted fans of the Southern University Jaguars and the Grambling State University Tigers for the annual Bayou Classic matchup between the Louisiana’s two historically Black state universities.

It seems an appropriate time to highlight a short-lived nonsectarian institution of higher learning called Columbia University, which existed from 1887 to 1889. In the 1880s, New Orleans was already home to four colleges: Straight University (founded in June 1869 by the American Missionary Association & Congregational Church); New Orleans University (chartered in March 1873 by the Freedmen’s Aid Society & Methodist Episcopal Church); Leland University (chartered in March 1870 by the Free Mission Society & Home Mission Society of the Baptist Church); and Southern University (chartered in 1880 as a state-run, nonsectarian institution). There was also the Peabody Normal School (established in 1877), which much like its similarly named white counterpart the Peabody Normal Seminary (established in 1870), offered a two-year post-secondary course for the training of teachers.

Southern University opened its doors in January 1881 on the upriver side of Calliope Street, between St. Charles and Prytania. Between its chartering in 1880 and the end of the 1885-86 academic year, the university had four active presidents: Dr. Alfred Richardson Gourrier, a Confederate veteran, surgeon, and sugar planter; George H. Fayerweather, a free man of color from Rhode Island, journalist and educator; Charles Henry Thompson, a free man of color from Pennsylvania, Oberlin graduate, and the state’s first Black Episcopal priest; Joshua Hicks Harrison, a Texan and graduate of Vanderbilt University.

In September 1886, the Reverend George W. Bothwell, an Ohio native and graduate of Adrian College and Yale University, was named president of Southern. The Reverend Bothwell had come to New Orleans in 1884 to serve as professor and dean of theology at Straight University and pastor of the Central Congregational Church. It was during Professor Bothwell’s presidency that Southern’s impressive campus at Magazine and Soniat streets (the cornerstone for which was laid on 8 May 1886) was dedicated on 14 March 1887.

Throughout June and July 1887, there were numerous open letters published in The Weekly Pelican regarding the awarding of the annual Peabody Medals for academic achievement. The Peabody Fund, established through the generosity of banker George F. Peabody, distributed medals to be presented the boy and girl with the highest standing in attendance, deportment, and general proficiency. There was an unawarded medal from the previous year and thus three medals to present. Professor Bothwell claimed that based upon the faculty’s recommendation, the three recipients were Miss Ellender Joseph, Joseph F. Barrow, and Bismarck R. Pinchback, a son of former Governor P.B.S. Pinchback. There were members of the university’s board who claimed that Bothwell made no such recommendation and that in keeping with Bothwell’s own report of the final averages, the young men with the highest scores were Joseph F. Barrow and Arthur Clement Williams.

Professor Bothwell published a letter in The Weekly Pelican lamenting the fact that young Pinchback was not awarded a medal. This public action on the part of Bothwell angered the trustees who narrowly voted for his dismissal, but as a compromise allowed his resignation to take effect on 1 January 1888. Bothwell apologized to the board, except for Louis-André Martinet, whom he refused to include. Martinet, who was also an attorney and former State Representative, seems to have been at the heart of the disagreement with Bothwell. The Daily Picayune reported allegations that Martinet’s dislike for Bothwell stemmed from conflicts between him and Martinet’s wife, who was a member of the faculty.

On 30 September 1887, a mass meeting to express support for Bothwell was held at Geddes Hall on Erato Street (between Carondelet and Baronne) under the auspices of James E. Porter and several other men who were leaders in the Longshoremen’s Protective Union Benevolent Association. Among the speakers was A. J. Kemp of Gretna, who maligned Martinet as “recognized sorehead and grumbler,” who wanted to be “president, teacher, trustee, and everything else.” He objected to a man who “pretended to be black one day and white on the morrow.” In an open letter, young Bismark Robert Pinchback, who was just shy of 19 years old, said of Martinet: “I would not give a fig for his honesty. What reliance can be placed in a man who professes no religion, who assumes himself to be infallible, and who has no respect for the people with whom he is identified by ties of blood. Mr. Martinet is known the State over as an erratic, peculiar person, who for the time being desires to be a Moses.” These are loaded accusations, the source of which was undoubtedly Pinchback’s father. The entire matter had the stamp of a sort of proxy war over intraparty politics rather than a pointed disagreement about university administration.

No time was wasted in planning the establishment of a new university to be led by Professor Bothwell. On 17 November 1887 another mass meeting was held at Geddes Hall, where a resolution was adopted to endorse the efforts to create the new school to be called Columbia University. The meeting was chaired by the Reverend Charles H. Thompson, a former president of Southern University. Among the speakers in addition to Bothwell and Thompson were Dr. Joseph H. Coker, Dr. Sterling P. Brown, Everett Samuel Swan, George Drew Geddes, Joseph Honore, Jr., and Miss Minnie Moore.

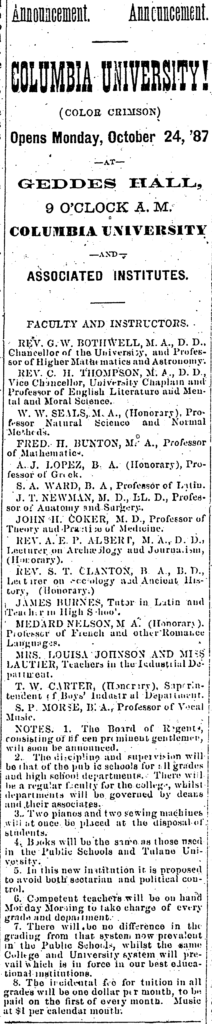

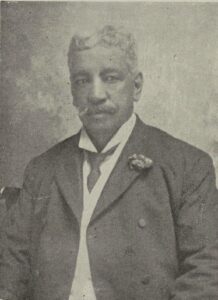

Within less than a week, the faculty and school color of crimson for “Columbia University and Allied Institutes,” was announced. The latter half of the school’s name reflected a desire on the part of Bothwell to form or affiliate preparatory institutes within the city as feeders for the new university, which was to be led by him as chancellor with Reverend Thompson as vice chancellor. The distinguished faculty included physicians John H. Coker and James T. Newman as well as revered educator Médard H. Nelson (French and Romance Languages) and journalist-minister A.E.P. Albert (archaeology and journalism).

- Professor Médard H. Nelson

- Reverend Charles H. Thompson, D.D.

- Aristide Elphonso Peter Albert, D.D.

Classes began on Monday, 24 October 1887 in Geddes Hall, a commodious and frequently used meeting place, which was a part of the large undertaking establishment conducted by George D. Geddes, Sr., in what is now the 1700-block of Erato Street. At the mass meeting prior to its opening, more than one hundred students had already been enrolled. French, stenography, sewing and embroidery, instrumental and vocal music were all offered in addition to the regular course of studies. Tuition was one dollar each month, a cost which was attributed to the fact that “Geddes Hall and the several anterooms [were] placed at the disposal of the faculty almost without cost.” Night classes began at Geddes Hall and in a downtown location to accommodate students in the lower half of the city. There was much comment over the accessibility of Columbia’s Erato Street campus, which could be reached via the Erato, Royal, and Bourbon streetcar lines.

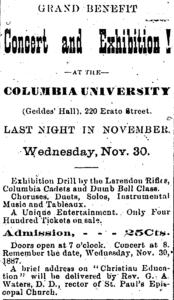

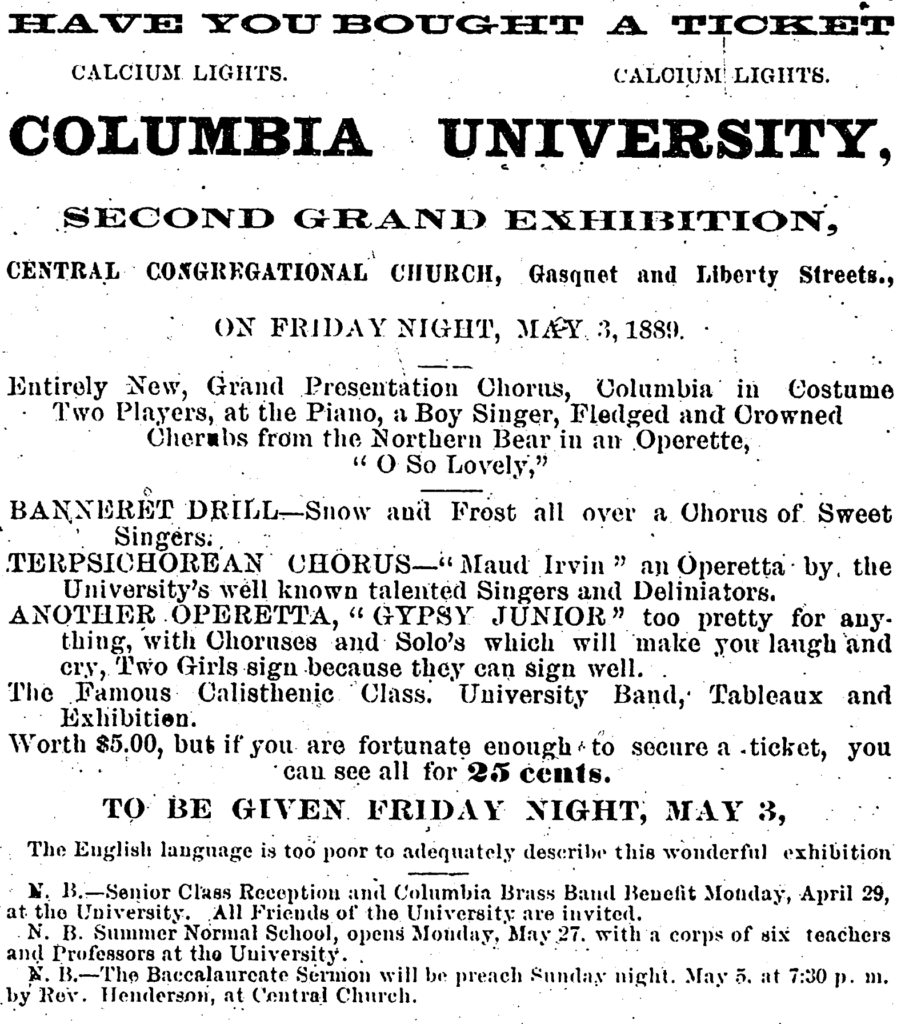

The first public event hosted by Columbia was a benefit in the form of a “Grand Instrumental and Vocal Concert” held in Central Congregational Church on 7 November 1887. Over two course of its two years of existence, several benefit concerts and exhibitions were held in Geddes Hall and at Central Congregational Church to raise funds for the school.

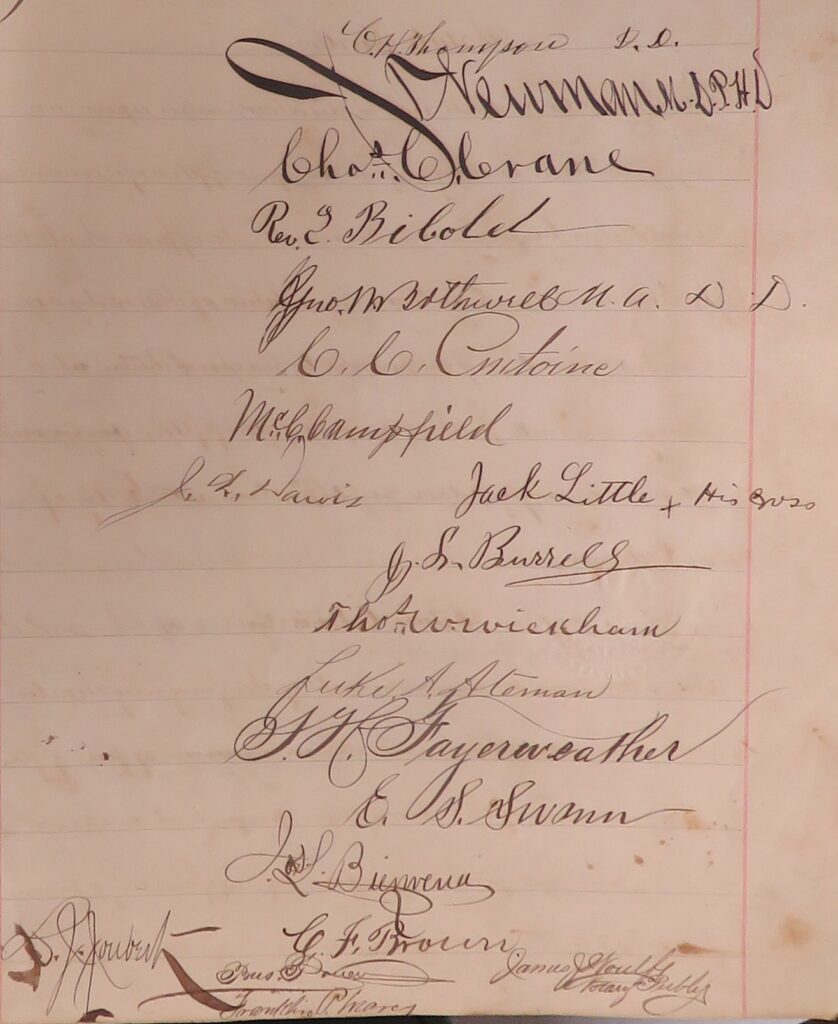

The healthy enrollment and attendance at the benefit concerts were encouraging to Professor Bothwell and the primary leaders, who appeared before notary James Woulfe on 25 April 1888 to formally incorporate the university. The purposes of the corporation were “to diffuse knowledge, to promote the cause of education, to establish in the City of New Orleans and in the State of Louisiana a non-sectarian non-political University open on equal terms to all races.” It was to be governed by a Board of Regents numbering between twelve and fifteen who were to serve staggered three-year terms. The following twelve men were the first regents of the university:

Luke Archer Ateman

Louis Joseph Joubert

Charles Calhoun Crane

Thomas Warrington Wickham

Honorable Ceasar C. Antoine

John Eugene Staes

Reverend John L. Burrell

Professor George H. Fayerweather

Dr. James T. Newman

Reverend Charles H. Thompson, D.D.

Reverend George W. Bothwell, D.D.

Reverend Leopold Bibolet

The other incorporators were McCornelius Campfield, J. L. Davis, Jack Little, Everett Samuel Swann, Joseph L. Bienvenu, and C. F. Brown.

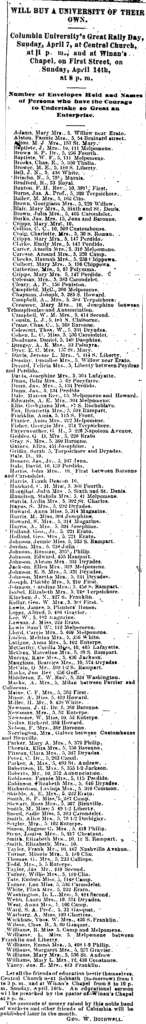

On 25 October 1888, Columbia University dedicated its new quarters in the old Melpomene Plantation home on Carondelet Street between Melpomene and Terpsichore. In April 1889, a campaign began in earnest to raise funds to have the university obtain its own campus. Rallies were held in Central Congregational Church on 7 April and in First African Baptist Church and Winan’s Chapel Methodist Church on 14 April to gather donations and pledges.

On 6 April 1889, the names of over a hundred donors were published in The Weekly Pelican.

Despite the enthusiastic support, Columbia’s existence was fated to be brief. In the spring of 1888, Reverend Bothwell accepted a call to serve as pastor of the Second Congregational Church in Oakland, California. He maintained the chancellorship of Columbia but split his time between New Orleans and Oakland. The vice-chancellor, Dr. Thompson, likewise moved on to become the pastor of St. Mary’s Episcopal Church in Vicksburg in the spring of 1889. The commencement exercises for Columbia University held in Central Church on 7 May 1889, marked the end of its brief but interesting history.

Jari C. Honora

Interesting that C.C. Antoine and Joubert were supporters of Columbia but Pinchback was not.

Jari,

Thank you so much for this interesting article.

I knew that my Grandfather, Thomas W. Wickham, had been involved somewhat in promoting education. But this lists him as one of the original Board of Regents. And lists my Grandmother as one of the people who pledged financial support.

One of my aunts, Isabella Wickham MacNeal, was related through marriage to the family of Arthur Clement Williams.

Nice article Mr. Honora.

Jari…Wonderful article …Great reporting as always!

Judy Geddes Bajoie…grgr granddaughter of George D. Geddes

This article is excellent. And it proves that HBCU’s were already being created in the deep south in a quiet but excellent way all along. I love this.